A sore back is one of the most common health complaints worldwide. Whether recent or long‑standing, back soreness often responds best to targeted rehabilitation rather than prolonged inactivity. This article summarizes expert insights and recent scientific findings, highlights the main benefits of active rehab, and explains sensible precautions. It also outlines why avoiding long periods of inactivity is important and presents the Malin Method as a structured, at‑home rehab approach.

Why back soreness occurs

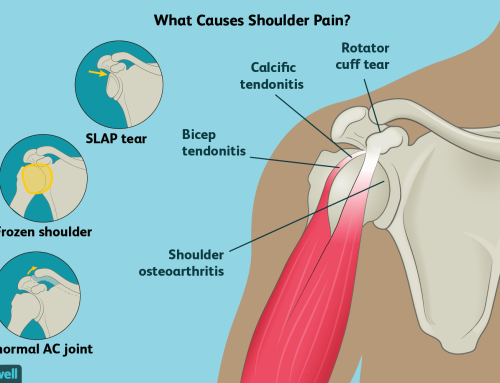

Back soreness (including low back pain) arises from many sources: muscle strain, ligament irritation, postural overload, disk-related problems, and movement‑pattern dysfunction. Psychological stress, poor sleep, and prolonged static postures can worsen pain perception. Identifying contributing factors—movement, strength deficits, ergonomics, and lifestyle—helps guide rehabilitation.

Recent scientific consensus and expert insights

Modern guidelines and systematic reviews emphasize active, function‑focused interventions for most types of non‑serious back pain. The Lancet series on low back pain (2018) and multiple systematic reviews have concluded that exercise, behavioral therapies, and individualized rehabilitation produce better outcomes for pain reduction and functional restoration than passive or purely pharmacological approaches. Exercise programs that include strengthening, motor control, flexibility, and graded exposure to normal activities show consistent benefits in both short‑ and long‑term outcomes.[1][2]

Main benefits of active rehabilitation for a sore back

- Reduced pain and improved function: Targeted movement and progressive loading reduce pain sensitivity and restore the ability to perform daily tasks.

- Restored strength and stability: Rehab improves deep trunk muscle control and overall spinal stability, decreasing recurrence risk.

- Improved movement patterns: Correcting faulty mechanics prevents overload and distributes forces more evenly through the spine and hips.

- Faster return to work and activities: Gradual, goal‑oriented programs help people return to normal activity sooner and with greater confidence.

- Psychosocial benefits: Active rehab reduces fear of movement, anxiety about reinjury, and the sense of helplessness that often accompanies chronic pain.

The dangers of prolonged inactivity for a sore back

Extended inactivity or avoiding movement because of pain may feel protective short term, but evidence shows it can be harmful long term. Remaining largely inactive leads to muscle weakness, loss of endurance, joint stiffness, reduced coordination, and decreased tolerance for loading. These changes make the injured area weaker and more unstable over time and can perpetuate chronic pain and disability rather than eliminate it.

Principles of safe, effective home rehab

- Assess and individualize: Identify movement limitations and pain‑provoking activities and prioritize functional goals (walking, lifting, sitting tolerance).

- Progressive loading: Start with low‑load, controlled movements and gradually increase intensity, range, and complexity.

- Motor control and stability: Train deep trunk muscles and coordination to support the spine during everyday tasks.

- Movement variability: Reintroduce varied positions and tasks to avoid over‑use of any single pattern.

- Consistency and pacing: Short, frequent sessions with incremental increases are more effective than sporadic intense sessions.

Malin Method: At‑home rehab system

Malin Method is a structured at‑home rehabilitation system designed to address movement dysfunction, chronic pain, and injury recovery across the body, including the back. It emphasizes progressive, accessible exercises, clear coaching cues, and a focus on restoring function rather than temporary symptom suppression. The program blends strength, mobility, and motor control work that aligns with current best practices for back rehabilitation.

Why the Malin Method is effective:

- Structured progressions that reduce the risk of overload while maximizing adaptation.

- Emphasis on movement retraining and functional tasks relevant to daily life.

- Scalable exercises that fit differing fitness and recovery stages, supporting long‑term adherence.

Sample safe exercises and cues (general guidance)

Below are examples of common components found in effective rehab programs. These are general suggestions—modify or avoid any movement that aggravates symptoms and consult a clinician for tailored guidance.

- Pelvic tilts and gentle lumbar mobility: Small, controlled pelvic movements to reintroduce comfortable range.

- Deep trunk activation: Learning to recruit transverse abdominis and multifidus with gentle loading (e.g., heel slides, marching in supine).

- Hip hinge patterning: Small‑range hip hinge with focus on hip and glute activation rather than bending at the spine.

- Quadruped and bird‑dog progressions: To train contralateral stability and coordination.

- Gradual loaded lifts: Progress from bodyweight movements to light external loads, emphasizing technique and symmetry.

Warnings and red flags — when to seek immediate professional care

While most sore back episodes improve with guided rehab, certain signs warrant urgent medical evaluation:

- Sudden severe weakness in legs or loss of bowel/bladder control.

- Progressive neurological deficits (numbness, significant motor loss).

- Fever with back pain, unexplained weight loss, or a history of cancer or immunosuppression.

- Pain after a major trauma or if pain prevents all movement.

Also avoid following advice that encourages high‑risk movements, rapid unmonitored increases in heavy lifting, or self‑treatment approaches that ignore persistent or worsening neurological signs.

Limitations and cautions about this article’s advice

This article provides general, evidence‑informed guidance but cannot replace individualized assessment. Complex structural problems, surgical candidates, and atypical presentations require personalized evaluation by qualified clinicians (physiotherapists, sports medicine physicians, spine specialists). If pain worsens despite progressive rehab, seek professional reassessment.

Practical next steps if you have a sore back

- Identify activities that increase vs. decrease symptoms and use that information to guide early exercise selection.

- Begin a progressive, movement‑based rehabilitation approach focused on strength, motor control, and function—consider structured programs like Malin Method for home‑based, progressive guidance.

- Monitor progress with objective goals (walk time, lifting tolerance, sitting duration) and adjust load gradually.

- Consult a clinician if red flags appear, progress stalls, or you need individualized progression.

Selected references and further reading

- Lancet Low Back Pain Series Collaborators. Low back pain: a call for action. Lancet. 2018;391(10137):2384–2388. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30480-X

- Hayden JA, et al. Exercise therapy for chronic low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021; (Updated reviews show consistent benefits). https://www.cochranelibrary.com/

- Trafficante R, et al. Multi‑component exercise interventions for chronic low back pain: systematic reviews and meta‑analyses (2017–2022). Evidence supports tailored, progressive programs for pain and function improvements. (See PubMed summaries.) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

Active, structured rehabilitation—applied progressively and with attention to safe loading and movement quality—is a primary evidence‑based strategy to relieve a sore back and reduce recurrence. Programs that combine strength, motor control, and functional progressions, such as Malin Method, offer practical at‑home frameworks that align with current scientific guidance.